LDC graduation and WTO enrolment

By Randall Krantz

On Wednesday and Thursday this week, Thimphu was graced by a biennial migration of development representatives from all corners of the world.

From the presentations by GNHC, MoF and MoEA, there was a demonstration of humility in the face of the challenges that lie ahead. During the statements from donor representatives, there were many announcements of continued support for Bhutan during the period of its 11th Five Year Plan and beyond.

One shadow that may have concerned some of the local representatives was the notion of Bhutan graduating from the ranks of Least Developed Countries (LDC). This will likely not happen for about a decade, and the timing is yet uncertain. Since the concept of LDCs was created by the UN in 1971, only three countries have ever shifted status from LDC to developing country status, though there are at least a dozen countries expected to graduate in the next decade.

Dr Richard Marshall, an Economic Advisor with UNDP, made a presentation outlining the process of LDC graduation. More interesting than the process, however, are the implications of graduation, which is a goal set out in Bhutan’s own 11th FYP. There is certainly an element of pride that comes with any graduation, but the question here is, at what cost?

According to Dr Marshall’s presentation, the biggest implications might be through trade and reduced Overseas Development Assistance (ODA). While Bhutan has a goal of being independent of assistance by 2020, this might not seem to be a cause for concern, but ODA continues to form a significant part of the country’s capital budget, especially as it is related to the hard infrastructure of roads, bridges and power.

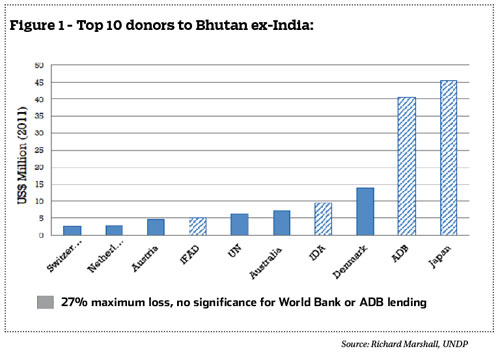

In total, 27 percent of Bhutan’s non-Indian ODA is potentially at risk and only 9 percent of all aid including India’s contributions. This is illustrated in the table above, with the dark columns indicating those funds most at risk.

Aside from the implications on direct funding, the most significant challenges of LDC graduation are related to trade. Trade tariffs on Bhutanese imports could be subject to change in various countries as well. The good news here is this would not affect trade with India, Bangladesh, or China, so increases in US or Japanese import tariffs would be insignificant, affecting less than two percent of trade.

The World Trade Organisation offers “special and differential” treatments to LDCs. For example, some countries receiving foreign investment, including Bhutan, imposed numerous restrictions on that investment designed to protect and foster domestic industries and to prevent the outflow of foreign exchange reserves. To counter this, WTO signatories are bound by Trade-Related Investment Measures, which limit the amount of protectionism allowed. LDCs are exempt from these rules and are given more leeway to be protective.

This brings us back to the other question that has been discussed in the news over the past week: Should Bhutan become a full signatory of the WTO?

The Bali Package, as it is currently known, presents several benefits for developing countries and two topics in the final agreement will have big potential impacts in the developing world. The first is trade facilitation, which, according to the OECD, could add $1tn to the global economy by cutting red tape at border crossings. This red tape tends to be most present in poorer countries and this is one area where Bhutan stands to gain. The second topic is a package of issues that are relevant to LDCs. These include duty and quota-free market access, preferential rules of origin and waiver concerning preferential treatment to services and service suppliers of the LDCs. The Bali conference reiterated that “developed countries should improve their existing duty and quota-free coverage so as to give access for at least 97 percent of products originating from the LDCs.”

It is still important to remember that the WTO is a one way street – it is not possible to test the waters and decide to go back. There are also cost and administrative implications as well. Participating in more meetings and preparing accounts and statements will require human and fiscal capital.

Clearly, WTO is slowly providing a better place for LDCs to become members of the global economy. In Bhutan’s case, with so much trade tied up with India, with whom there is already a free trade agreement, there is still much to consider. As the country targets increases in exports and more of those going beyond India to other countries is Asia, Europe and beyond, the WTO could provide certain advantages.

While in Bali at the latest WTO negotiations, the economic affairs minister pointed out that it is not a question of whether, but rather of when Bhutan moved from being an observer to a signatory. Given the results of the latest negotiations and Bhutan’s short-termed LDC status, there is a strong argument that now is the best time to join.