GNH: a bad idea whose time has gone

By Alan Beattie

Raising a standard against happiness is never going to be popular, but here goes.

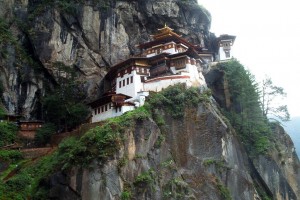

The mountain kingdom of Bhutan has got a lot of mileage out of its practice, first adopted in 1972, of using a broad “Gross National Happiness” (GNH) measure of its people’s welfare rather than a narrow measure like income.

According to the many people who have fallen in love with the idea – the UN went as far as declaring March 20 the “International Day Of Happiness” – a holistic approach to welfare reflects more accurately the many dimensions of wellbeing in the human condition. The philosophy has been urged upon rich and developing economies alike as the proper goal of government policy.

Unfortunately for its international enthusiasts, its originators are losing faith. Tshering Tobgay, elected with a thumping majority last year in only the country’s second parliamentary election, has distanced his government from the concept. “If the government of the day were to spend a disproportionate amount of time talking about GNH rather than delivering basic services, then it is a distraction,” he said. “Rather than talking about happiness, we want to work on reducing the obstacles to happiness”. His campaign promised more practical advances including a motorised rototiller for every village and a utility vehicle for each district.

This is a welcome development for two reasons. One, Bhutan’s GNH, defined from the top by an autocratic monarch, was a deeply illiberal means of legitimising undemocratic rule and failed utterly to prevent grotesque abuses of human rights. Two, it has distracted from much more constructive and democratic ideas of running countries in the interests of their citizens’ wider wellbeing.

Mr Tobgay’s disillusionment underlines the obvious problems with trying simultaneously to hit a bunch of vaguely-defined targets (for which see also the Millennium Development Goals and their successors) – but even more so of allowing authorities to decree what they consider the happiness of their citizens to be.

The GNH is assessed by asking survey respondents about a variety of indicators, from more conventional issues like health and education to more nebulous concepts like emotional fulfilment and perceived national ecological sustainability. It is noticeable that the haziest ones seem to do better: the highest-scoring indicator is “Values”, denoting that Bhutanese tend to concur that murder, stealing, lying, creating disharmony in relationships and sexual misconduct are a bad thing. Good for them, but, on the other hand, less than half of respondents are happy with their literacy, employment opportunities, government services and schooling.

Such outcomes are hardly surprising: the autocratic monarchy that ruled Bhutan until the first free elections in 2008 substantially failed to deliver better lives for most of its duration. Literacy is still only around 50 per cent, and only around half of children attend secondary school. Most Bhutanese are still subsistence or other small-scale farmers, unemployment is rife and suicide rates are alarmingly high. Corruption in government is believed to be widespread.

Moreover, GNH has proved no guarantee of individual human rights. Taking it at face value, you would never know that Bhutan has for decades been carrying out a brutal ethnic cleansing policy against the country’s Nepali-speaking minority. Once around a sixth of the population, a “Bhutanisation” campaign that began in the 1980s resulted in tens of thousands of Nepalis being expelled from the country. Their houses were seized or burned down and people deported for speaking Nepali, refusing to eat beef (Nepalis are generally Hindu while ethnic Bhutanese are Buddhist) or declining to wear traditional dress. The displaced are still living in refugee camps in Nepal, or have been resettled in the US or elsewhere: none has been allowed to return.

GNH defines and imposes a unitary set of values that does not protect diversity or individual rights, or at least addresses them only in ways that can be defined and controlled by the government. It is a communitarian view of the world distinctly reminiscent of Hu Jintao’s ideal of a “harmonious society”, a concept frequently cited by the Chinese government when clamping down on free speech and dissent. It should give GNH’s foreign supporters a long pause for thought that as soon as Bhutanese voters had a choice after decades of dictatorship, they threw out its backers and brought in its critics.

The international attention given to GNH is doubly irritating because it has managed to distract attention away from more transparent and participative attempts to measure wellbeing, coordinated among others by the OECD. Several governments have made serious attempts to work out what makes their citizens happy by the novel procedure of asking them, not defining it on their behalf.

The best way of finding out what makes people happy is watching what they do, or what they spend their money on. It’s notable, for example, that the perennial surveys of the world’s most liveable cities, which always seem to end up recommending Copenhagen and scorning London, are generally at odds with where internationally mobile people actually choose to live. The criteria of the survey’s designers are evidently not the same as those of real people actually making decisions.

Of course, not every expression of wellbeing can be judged or delivered by the free market. Services like universal healthcare do not function well in the private sector, and there are negative growth externalities like pollution, noise and traffic which require a wider measure of welfare. Still, the guiding principle is that concepts of wellbeing need to be expressed through the market where possibly and democratic choice where necessary, not imposed by technocrats – and particularly not used by autocratic governments to suppress individual choice.

As for the future of GNH in Bhutan, Mr Tobgay seems to have exactly the right idea. He wants the king (now happily reduced to the role of a constitutional monarch) to proselytise for it in an abstract way, much as Queen Elizabeth II is sent abroad to chunter vaguely about Britain’s enduring values while the UK government gets on with running the country according to what its voters want.

Poor farmers need more motorised rototillers to work their land and fewer autocratic monarchs commanding them to be happy in a manner decreed by the state. Measures of wellbeing need to be debated and tested rather than dreamt up and imposed. Bhutan’s “Gross National Happiness” has attracted praise from gullible foreigners, but at home it has acted as a cover for serious failures of governance and severe abuses of human rights. Its demotion is entirely to be welcomed.

Source: Financial Times